THE world's most populous nation is suffering from a shortage - of people.

The workers who churn out bras for the British high street and toys to go

under the Christmas tree are no longer happy to work in factories where security

guards keep them behind locked gates or where taking a lavatory break of more

than a minute could mean a fine.

Since China has been transformed into an industrial juggernaut, demand for

labour has soared so that it outpaces supply. This may not be the case in every

province, but it is becoming a pressing problem for factories in the prosperous

south, which rely on migrant workers.

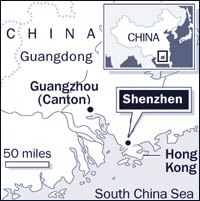

In the boom town of Shenzhen the labour department is considering raising the

minimum wage - already the highest in China at £50 a month. That compares

with £16 that China's 750 million farmers take home on average, but young

peasants just off the bus say that it is scarcely worth getting out of bed for.

Zhang Wen is 22. Dressed in plastic high heels, jeans and a sequined pink

T-shirt, the young woman from central Hunan province joined thousands of others

at the Shenzhen labour exchange. "I didn't like my last job selling houses

so I resigned. I have some education and I think I can do better than that."

She has been coming to the exchange every day for a week looking for a job that

will pay at least £70 and says she won't settle for much less. "If I can't

find a good job then I'll go farther north."

One reason for the labour bottlenecks in southern Guangdong province, which

abuts Hong Kong, is China's race to industrialise. The breakneck growth has

created jobs in provinces all along the coast, many in new cities where living

standards are much lower than among the skyscrapers of Shenzhen. Many young

people prefer to stay closer to home rather than move south.

That is one reason why Guanri Telecom-Tech Co, China's biggest exporter of

payphones, has decided to shift a chunk of production to the poorer inland

province of Jiangxi.

There are only nine workers available for every ten jobs on offer in

Guangdong and the situation is getting worse. Migrant labour is the lifeblood of

Shenzhen, which in 25 years has grown from a fishing town of 30,000 people to a

city of around 12 million, dotted with Burberry outlets and Starbucks coffee

shops.

As with many towns and cities in southern China, Shenzhen is a victim of its

own success. Chen Jun Bo, owner of the successful Jane Story clothing chain,

said: "We've taken 20 years to achieve the growth of 100 years.

Infrastructure and people can't keep pace."

Brawn is easily available and university graduates are two a penny, but

skilled workers with technical training are at a premium. Mr. Chen said: "The

Government doesn't have the resources to train and encourage young people, so

it is up to enterprises to solve this problem."

His solution is to recruit in schools and colleges in smaller cities. His

company signs contracts - sometimes with an entire class - and then keeps an

eye on potential staff until they finish school. "It's less expensive to

keep track of them than to have to keep going out to the market to hire

untrained people."