El Raval

|

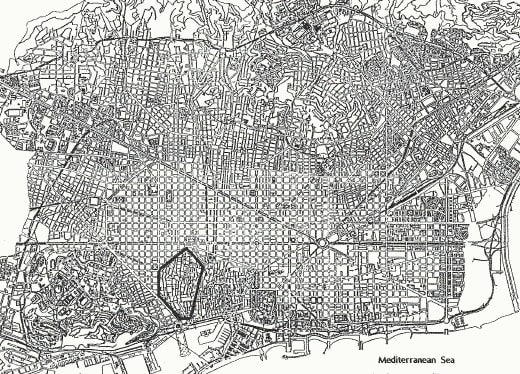

| Location of El Raval |

|

| El Raval, Barcelona: Google Earth |

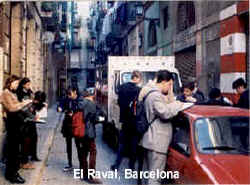

The district of El Raval, located in the medieval city quarter of Barcelona, was until recently one of the most densely populated urban areas in the world. Recent and ongoing regeneration schemes have dramatically altered the social, environmental and economic characteristics of some parts of the area. However, the wider effects of the schemes have yet to fully reach many of the streets, which remain little touched since the Middle Ages. Shafts of sunlight filtering into the narrow passage-ways give a sense of drama usually reserved for film sets.

In 1800 much of El Raval had not been built up, but consisted of small market gardens that supplied the city. By 1850 the Industrial Revolution was leading to El Raval rapidly filling with tenement blocks (for the workers from the countryside) and textile mills, powered by coal. These buildings were built several storeys high to maximise space, for this was the district for the new industries of a Barcelona still tightly contained within its defensive walls. The tenement blocks were high-rise slums. Toilets and a tap were shared in the courtyard of each block. Epidemics were frequent and the death rate was high - many dieing in their late teens.

The textile mills competed for space with older industries, such as brick making, slaughtering and tanning leather, considered too dangerous or polluting to be allowed in the Barri Gotic old city area where the wealthier inhabitants lived.

The southern half of El Raval, nearest the port, achieved a reputation as a centre of low-life and the sex industry, with high-class brothels for the rich and far worse conditions for the poor in the hundreds of bars and hostels. The area is also known as ‘Barrio Chino’ or Chinatown. This label was given to the area (which has no Chinese connections) in the 1920’s by a local journalist, Francesc Madrid, after he saw a film about vice in San Francisco’s Chinatown, and was swiftly adopted. Barcelona has always had an underworld centred in El Raval.

Today much of the area has changed enormously. It still has an industrial flavour, but its surviving industry consists of small old-fashioned workshops in trades like printing, furniture or building supplies. Most of the old tenement blocks remain, although many have been demolished. There is a growing trend to modernise those blocks in best condition, but many remain with old electric wiring, poor or inadequate water supply, and ten apartments linked by one stairway to a street entrance. None of the tenements have fire escapes.

The biggest change has been in the ‘Barrio Chino’, which has been a prime target of the Government’s urban renewal schemes. Serious problems began for the ‘Chino’ at the end of the 1970’s, with the arrival of heroin. The area’s old, semi-tolerated petty criminality suddenly became much more threatening, affecting the tourist trade in particular. The Government acted swiftly and since 1988 most of the areas cheapest hostels have been closed, and whole blocks associated with drug dealers or prostitution have been demolished to make way for new squares. The people displaced were often transferred to newer flats on the outskirts of the town, out of sight, so perhaps out of mind.

Another element in what the authorities call the esponjament

(mopping up) of El Raval has been directed gentrification, with the

construction of a students’ residence, a new police station and office blocks

on the demolished sites. Further developments in the most notorious areas are

planned, including a 14-storey hotel.

Some of the changes have undeniably been for the best. One person who has just felt the benefits is Avelina Perez, a lifetime Raval resident, cleaning lady and mother of a family. "We moved into our new place two months ago and even though it’s actually a little smaller than the old one, the difference is literally like night and day. For a start, we now get sun coming in, instead of just the smell from the rubbish containers and drains. Also, my 18-year-old son is disabled and in the old flat I had to put him over my shoulder and carry him up and down from the third floor. And, well, he weighs 70 kilos now. Thank God for the lift."

Avelina Perez’s old flat was in Carrer Cadena, a street that has become one side of El Raval’s new Rambla, completed in 2000. The new housing will not in itself bring new residents into the barrio - it is reserved for long-term residents, mostly elderly people, who have been displaced by demolition.

Whether a real regeneration will follow is arguable. "In places like Calle Sant Ramon, they’ve put in trees and created a plaça - and the criminal elements have moved straight back in again to fill it," says Pep Garcia, president of the Associacio de Veins del Raval. "The projects need to be accompanied by a lot more social and police action or it won’t achieve anything." There is still a lot of petty crime on the streets, associated with a small group who are worst off, not specifically with immigrants.

To many people, the cumulative effect of the urban renewal schemes, particularly the construction of a wide pedestrianised ‘Rambla’ through ‘Barrio Chino’, (1999/2000), has been to rip the heart out of one of the more unique parts of the city, and to leave it looking rather empty.

Another, unpredictable change in El Raval, however, has been the recent appearance of a sizeable Moslem community, mostly of Moroccan and Pakistani immigrants, who have taken over flats no longer wanted by Spaniards. There is also a sizeable Filipino community. The area’s low-rents and central location with easy access to nearby work, have always attracted different waves of immigrants and transients.

Typically these new immigrants face a whole set of difficulties that earlier migrants mainly from the south of Spain didn’t have: legal and language problems, culture shock and racial prejudice. On the other hand, some local people feel the neighbourhood’s established way of life is threatened by the arrival of large numbers of newcomers. But SOS Racisme says: "there are cases where immigrants have been living fifteen in a flat. It’s bad, it’s unhealthy, but the way some people have criticized them for it, they forgot that just a little while ago, whole families here were sleeping in one- room flats."

The main road of the lower Raval, Nou de la Rambla, today has only a fraction of its earlier life, but retains a surreal selection of shops — theatrical costumiers where strippers can buy their sequin, alongside fashion shops that specialise in bridal wear. The main road in the upper Raval, Carrer l’Hospital, is now a very sought-after location for many businesses linked to the tourist trade. Towards Plaça Catalunya is the site of the largest-scale official projects for the rejuvenation of the area, with the building of the giant cultural complex that includes both Museu d’Art Contemporani and the Centre de Cultura Contemporania. It is also to be the location for an El Raval Humanities University. The rejuvenated upper Raval contains many several quality food shops. Carrer Doctor Dou, close to the Art Museum, has turned into virtually a whole street of small art galleries.

The Centre de Cultura Contemporania is the first centre in Europe to address the urban culture as a driving force behind change and a generator of social, urban planning and cultural developments. It has become a point of reference on the international scene and, with its commitment to the city, has contributed to a new cultural circuit and tourist itinerary in a re-emerging El Raval.

As well as acquiring a completely new association with sophisticated culture, parts of the district have enjoyed a new lease of life thanks to their bars having been rediscovered as places for slightly ‘down-market’ (‘grunge’ culture) socializing. Many artists have set up studios along Carrer Riereta. "It began in the 1980’s, when art school graduates began to rent these light industrial spaces with big windows," explained art critic Jeff rey Swartz. "There are around forty artists in lower Carrer Riereta at the moment, and many more dotted all over the barrio, although big cheap spaces are now much harder to find."

The area is also popular with immigrants (such as teachers) newly arrived from elsewhere in Europe who find the atmosphere of the area, with its lack of traffic and medieval quality far more appealing than the Spaniards brought up as children in the area. Typically, such young Spaniards are only too ready to move out to the suburbs as soon as they can afford to do so.

The urban regeneration of El Raval has been led by public funding including money from the EU social cohesion fund. Today, private investment greatly exceeds public investment. Government action has concentrated upon improving infrastructure, municipal and district facilities, housing, employment, health, education, social services, sports facilities and restricting criminal and marginal activities. Campaigns have been launched to restore the image of the neighbourhood. The promotion of the historic and cultural heritage has resulted in increased tourist use.

The effects have been profound. Depopulation continues, but in a sustained way in absolute terms and in relation to the depopulation of Barcelona in general. Employment has risen significantly but due to the low qualifications generally found amongst the inhabitants, jobs created in the district often go to workers from other areas. Family income is clearly falling. The housing market is tending to rise. The crime rate has reduced to the Barcelona average and criminals have been effectively exported out of the area. Moves continue to rid the area of ‘marginal’ activity. Perceptions of individual security have improved as have collective perceptions of the neighbourhood. Levels of education show important inequalities with respect to the average for the city as a whole, but these have gradually improved in recent years. Health statistics are influenced by the characteristics of the population with the high proportion of people older than 64 years (28%), the high number of people over 74 years who live alone (35.9%) and average family purchasing power below that of the city as a whole. The incidence of serious illnesses such as Aids and tuberculosis is significantly higher (2 to 7 times) in El Raval than the city as a whole. There are many cases of malaria, an illness linked to immigration. Mortality is higher in El Raval than in the city of Barcelona as a whole. South El Raval has the worst health indicators in the city. Actions launched have had a positive effect however and current policy and programmes are aimed at combating new health problems (tuberculosis, drug addiction, etc.).

The typical problems of people living in El Raval are, in this order:

1. economic (low income and problems with occasional debts);

2. health;

3. social (e.g. isolated from family);

4. unemployment;

5. housing;

6. social psychology (problems within the family);

7. legal issues (conflicts between landlords and tenants, lack of work permits);

8. schooling (truancy and educational backwardness).